As we finally emerge from the pandemic with the lifting of lockdown restrictions and the gradual resumption of everyday life, many of us carry mixed feelings on the matter. On the one hand, we greatly anticipate being able to gather again in the physical presence of our family, friends, and colleagues. On the other hand, many of us are also apprehensive about resuming social contact after having been isolated for more than 18 months, and fear contracting Covid or spreading it to our loved ones. Having borne witness to the tragedies wreaked by Covid, of lives lost, and the millions who continue to suffer the devastating consequences of Long-Covid months after first contracting the virus, there are many who now fear human contact, perceiving them as hosts of this invisible threat.

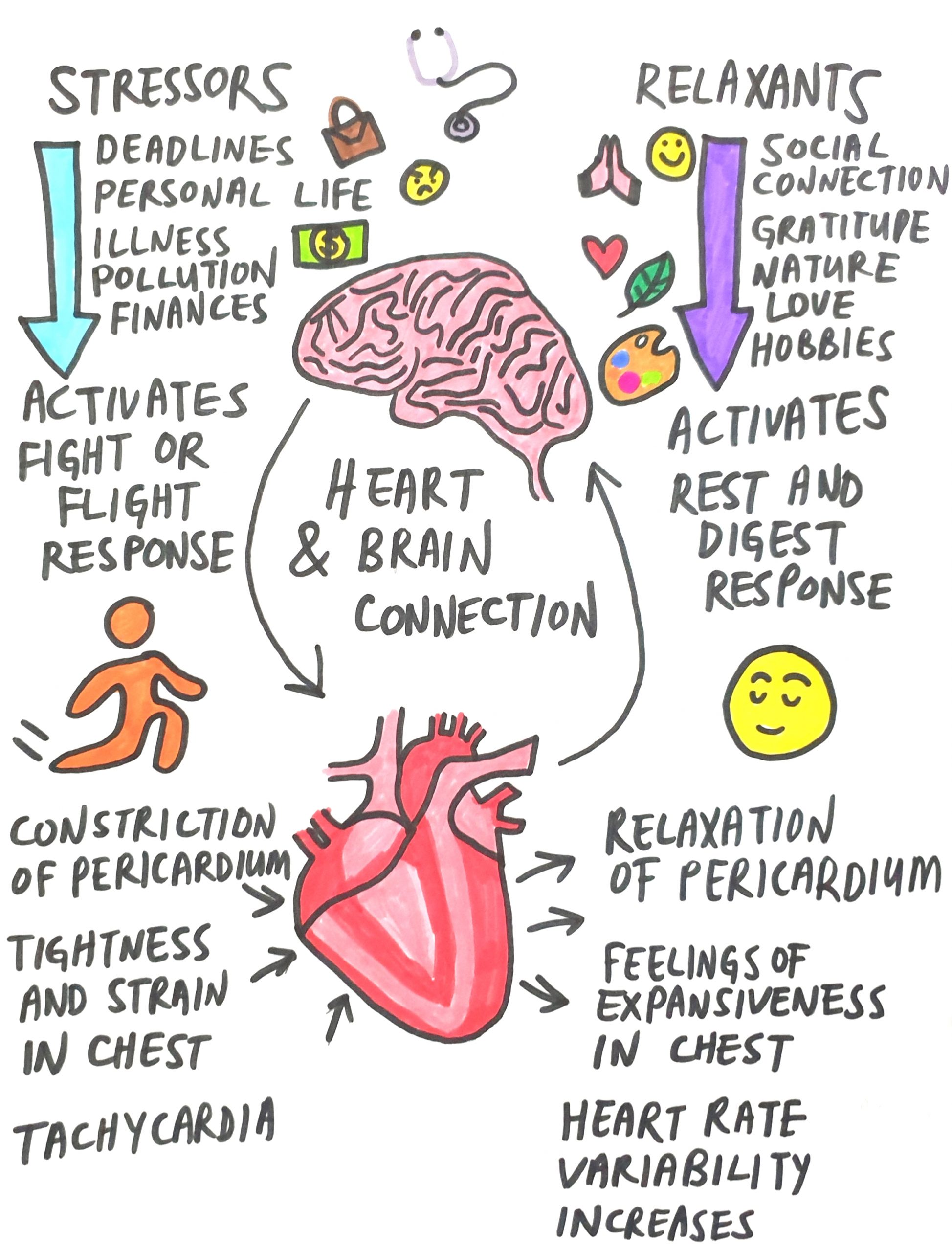

Having treated hundreds of Long-Covid patients over the past year at the clinic, I have noticed two groups of patients come through our doors. The first group has Long-Covid, with all the physical pathologies associated with the condition. The second group on the other hand, can be described as being self-diagnosed with the virus, and no doubt suffer from the physical symptoms of fatigue and anxiety. Their anxieties about Covid have been perpetuated by the barrage of negative media headlines, contradictory government communications on the matter, as well as the financial stresses associated with the global economic downturn, resulting in a constriction of their hearts through the tensing of the pericardium, the membrane surrounding the heart, and the hyperactivation of their nervous systems.

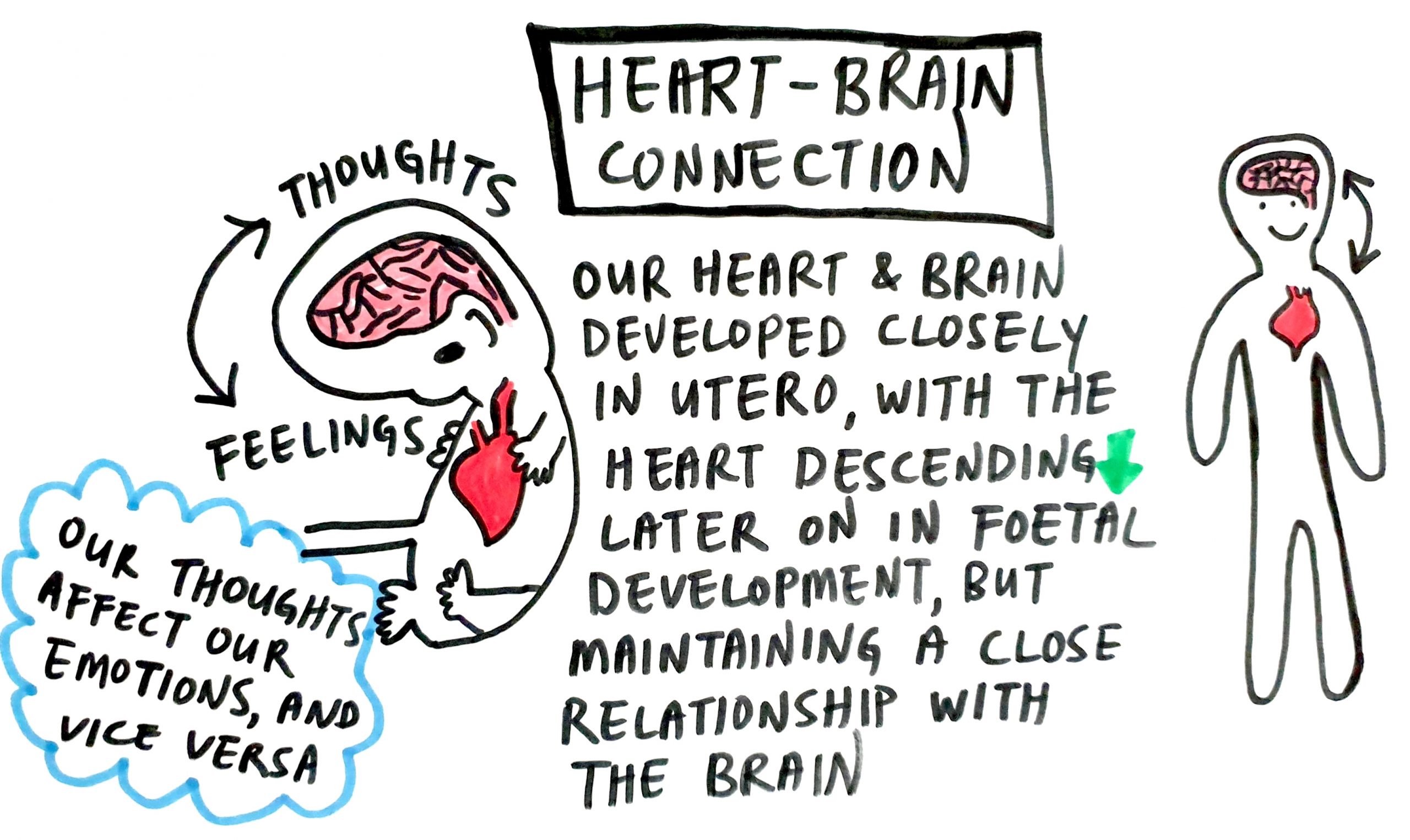

Tuning into my patients during treatment, I have felt the inextricable link that exists between the brain (central nervous system) and the heart. Stressful events and traumas of a mental and emotional nature result in the constriction and compression of the pericardium, which places mechanical stress on the heart. This can manifest in symptoms such as a sensation of tightness in the chest, chest pains, and tachycardia (fast heart rate). Additionally, with the hyperactivation of the nervous system, the flow of spinal fluid is affected, resulting in cognitive impairment manifesting in symptoms such as brain fog, and impaired speech; we have all experienced being at a loss for words when in a state of fear and anxiety. We often forget about the feedback loop that exists between the heart and the brain; our emotions affect our thoughts, and vice versa. The inseparability of both organs is established in utero; the heart develops in close conjunction with the brain, and descends afterwards, but the link between both organs still remains.

In many of these patients, this hyperactivation has resulted in a state of dysautonomia, which is a dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system. Dysautonomia is prevalent amongst my Long-Covid patients too, and is associated with symptoms such as fatigue, frequent vague but disturbing aches and pains, tachycardia, dizziness and faintness, hypotension (low blood pressure), poor exercise tolerance, numbing and tingling sensations, blurred vision, gastrointestinal symptoms, anxiety, and depression.

The autonomic nervous system controls all the involuntary functions in our body such as heart rate, breathing rate, blood pressure, and the dilation and contraction of key blood vessels and airways in our lungs called bronchioles. It can be split into two branches; the sympathetic nervous system, better known as the fight-or-flight response, and the parasympathetic nervous system, better known as the rest-and-digest response.

Sympathetic Nervous System

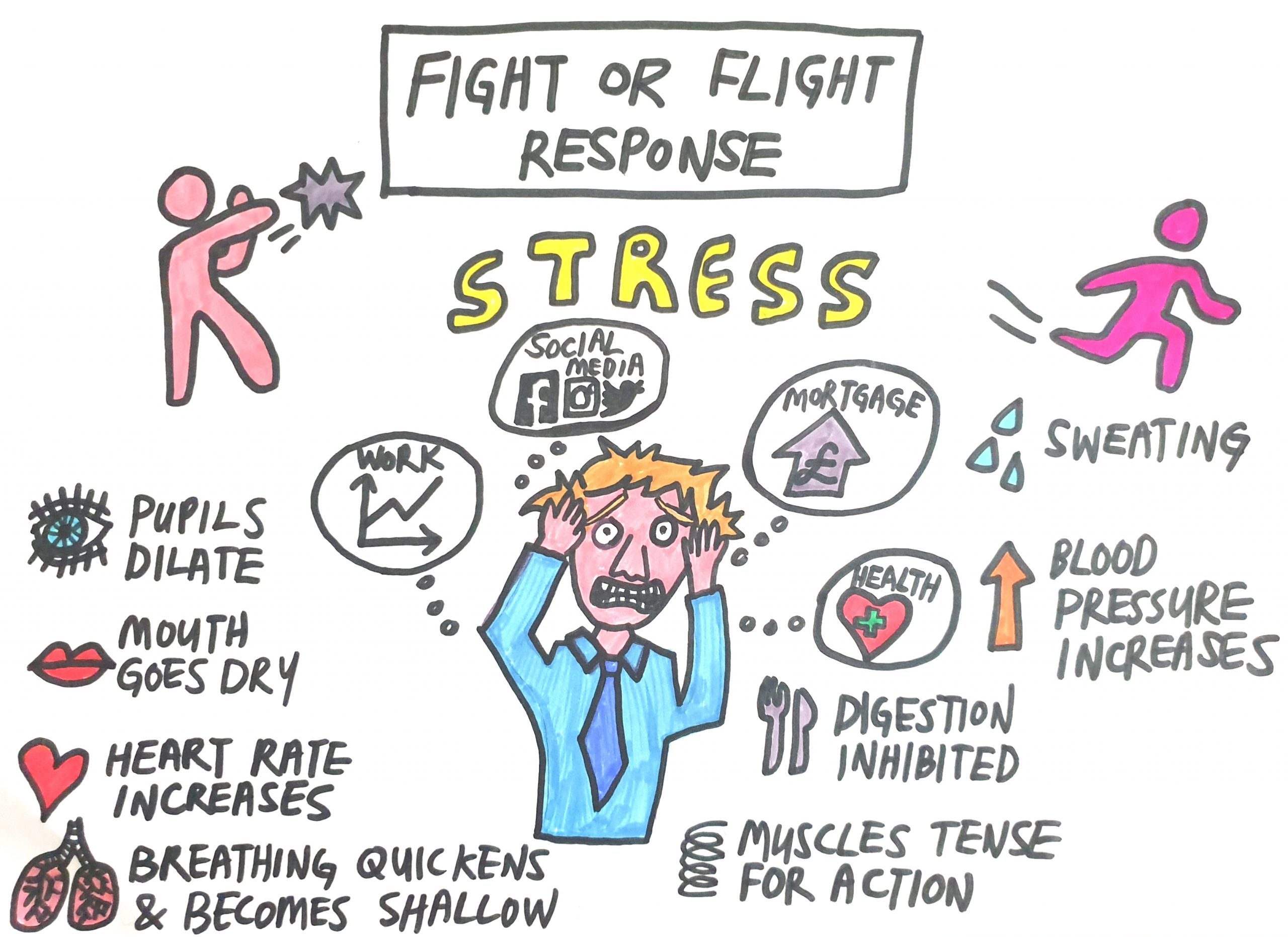

The sympathetic nervous system is activated in response to perceived threats in our surroundings, and was developed as an evolutionary response to help our ancestors survive in the face of life threatening situations by enabling them to react quickly to threats and to garner the physical resource to fight off or flee from threats such as a fearsome tiger or warring tribes.

When we experience a stressful event or encounter a dangerous situation, our eyes and ears send this sensory input to a primitive area of our brain responsible for emotional processing known as the amygdala, which interprets these images and sounds and immediately sends out a distress signal to the hypothalamus, our brain’s command centre. This process happens instantaneously beneath the level of our conscious awareness and is what enables us to react with the speed necessary to ensure our survival; for example, when we instinctively jump away from an oncoming vehicle before our minds have the chance to process what is happening. This immediate response is known as the amygdala hijack, as it bypasses our frontal lobes, which form part of the cerebral cortex; this newer, rational part of our brain is where logical thinking, reasoning, and decision-making takes place.

Upon receiving the distress signal, our hypothalamus activates the sympathetic nervous system by sending signals to our adrenal glands which respond by pumping adrenaline into our bloodstream. The circulation of adrenaline in our bloodstream brings about various physiological changes. Our heart begins to beat faster and the blood vessels in large muscles dilate, while blood vessels in the rest of the body in areas such as our digestive and reproductive organs constrict. The functioning of these systems require significant energy resources and are not a priority when we are faced with an existential threat, so the body redirects their blood flow to other areas of our body.

Blood flow to our muscles is promoted and causes our heart rate and blood pressure to increase. Our pupils dilate so we can take in more visual cues from our surroundings and respond to them. We begin to breathe more rapidly, and our bronchioles dilate so our body can receive more oxygen. Adrenaline also triggers the release of blood sugar from our liver and other storage sites in our body. The increase in oxygen and blood sugar availability results in more energy being produced by our body via the process of cellular respiration.

After the initial surge in adrenaline subsides, if the brain continues to perceive danger, the hypothalamus then releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which travels to the pituitary gland, triggering the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH then travels to the adrenal glands and signals for them to release cortisol, our body’s stress hormone, which keeps the body in a state of high alert until the brain no longer perceives danger. With the passing of a dangerous situation, cortisol levels fall, and the parasympathetic nervous system is activated.

Parasympathetic Nervous System

The parasympathetic nervous system works to counterbalance the effects of the sympathetic nervous system and is responsible for bringing the body back from a state of emergency to a state of homeostasis. It modulates our inflammatory responses, our immune system, and ensures the optimal functioning of our digestive and reproductive systems. Our pupils constrict as we are no longer in a state of high alert, our heart rate decreases, our bronchioles constrict, our salivary glands activate, our digestive organs increase their secretions and our intestines increase their peristaltic activity.

The parasympathetic nervous system works to counterbalance the effects of the sympathetic nervous system and is responsible for bringing the body back from a state of emergency to a state of homeostasis. It modulates our inflammatory responses, our immune system, and ensures the optimal functioning of our digestive and reproductive systems. Our pupils constrict as we are no longer in a state of high alert, our heart rate decreases, our bronchioles constrict, our salivary glands activate, our digestive organs increase their secretions and our intestines increase their peristaltic activity.

The parasympathetic nervous system is the natural state our bodies should be in when in a state of rest and recovery, and is also the state where we are able to think most creatively and logically, and resolve problems as we are not not clouded by emotions in reaction to external events.

Unfortunately, in modern times most of us now spend too much time with an activated sympathetic nervous system, in survival mode despite the fact that we are not constantly surrounded by life threatening dangers. This hyper-sensitivity of our autonomic nervous system can be attributed to the fact that our ancestors needed a nervous system that was able to fire back within a split second of encountering a perceived threat if they were to survive.

In the past, once these threats, such as encountering a fearsome tiger had lapsed, our nervous system would automatically shift from a state of fight-or-flight to rest-and-digest. This flexibility and moment to moment dynamism of the sympathetic and parasympathetic components of the autonomic nervous system, shifting from moment to moment depending on the body’s instantaneous needs, is a marker of its health.

Dysautonomia

In patients suffering from dysautonomia however, the autonomic nervous system loses its balance and results in the inappropriate predominance of either the sympathetic or parasympathetic response. In most of my patients, it is the sympathetic nervous system which dominates, with the body constantly being on high alert due to their perception of being surrounded by life threatening danger despite it not being the case.

Stressful situations such as traffic jams, deadlines at work, financial challenges, difficulties in one’s personal life, excessive social media use, and the threat posed by unknown circumstances all contribute towards the dysregulation of our nervous system. Prior to the pandemic, these background factors already predisposed most people towards a predominance of their sympathetic nervous system, and is associated with conditions such as hypertension, obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, heart disease, kidney disease, obstructive sleep apnea, ulcerative colitis, anxiety, depression, and even Parkinson’s disease.

The extraordinary circumstances of prolonged global lockdowns and social distancing measures imposed upon us with the emergence of the novel threat posed by the pandemic, however, threw the world into a state of sympathetic overactivation, with all its aforementioned health complications.

Resources

It is therefore imperative for us to learn how to regulate our nervous system and bring it from a state of sympathetic overdrive to a state of restorative equilibrium only possible when our parasympathetic nervous system is activated.

Below are some resources that can help you in this process:

Time in nature

- Studies have established a positive connection between spending time in nature and stronger feelings of connection with our community and the wider world, an increased capacity to cope with life’s demands, and with greater levels of empathy and altruism. Time spent in nature is also associated with positive moods, psychological well-being, meaningfulness, and a sense of vitality.

- Studies using fMRI to measure brain activity indicate that when participants viewed scenes of nature, the parts of their brains associated with love and empathy lit up. Conversely, viewing cityscapes resulted in the lighting up of parts of the brain associated with fear and anxiety.

Social Support

- Research has documented many physiological and mental health benefits of spending time with your friends and loved ones. These include improved immune, cardiovascular, and neuroendocrine function, as well as decreased levels of anxiety and depression.

- Creating strong relationships and cultivating a circle of supportive friends may take some effort but is one of the best ways to enhance your health and wellbeing.

Meditation

- Mindfulness practices reduce the activity in the amygdala, the part of our brain that triggers the activation of our sympathetic nervous system, and so reduces our levels of stress.

- Recalling the connection between the heart and brain, meditations which generate feelings of gratitude and unconditional loving kindness (e.g. metta meditations) are especially helpful in relaxing the pericardium, which places less stress upon the heart. This in turn helps to liberate us from negative thought patterns by disrupting the feedback loop that exists between both organs.

- Mindfulness also enables us to become more aware of our thoughts, which can help by giving us a more objective perspective on situations which we would normally have reacted to in anxiety. The cultivation of objectivity helps to prevent the stress response from being activated.

- Fascinating research in 2012 revealed that the perception of stress having negative health effects is independently associated with an increased likelihood of worse mental and physical health outcomes. Survey respondents who reported high levels of stress and who also believed that stress had a negative impact on their health had a 43% increased risk of dying prematurely. On the other hand, survey respondents who reported having high levels of stress but who did not view their stress as harmful had the lowest risk of death of anyone in the study, even lower than those who reported experiencing very little stress. This research highlights the importance of cultivating a healthy attitude towards stress.

Visualisation

- Visualisation is a powerful technique that helps in reducing stress levels by the use of active imagination. According to research using brain imagery, the neurons in our brain interpret the imagery being invoked during visualisation as equivalent to real-life action. Thus, even in the face of stressful situations, the ability to visualise a tranquil scene enables us to keep calm and stay present.

- Studies have shown that novice surgeons and police officers who received visualisation training demonstrated reduced levels of self-reported stress and decreased levels of objective stress.

Osteopathy

- Osteopathy detects, treats, and prevents health problems by the moving, stretching, and massaging of a person’s muscles and joints to ensure that all bones, muscles, ligaments, and connective tissue functions smoothly together. This enhances the body’s natural resources and optimises health, alignment, movement, and energy.

- Through the gentle manipulation of the vagus nerve, which is an integral component of our parasympathetic nervous system, osteopathy helps to bring the autonomic nervous system back into a state of homeostasis.

- Treatments also help to reduce anxiety and its impact on the body by assessing the body’s overactive nervous system and its associated symptoms, and correcting them through gentle manipulation.

Yoga, Qi Gong, Tai Chi

- According to Vedic and Traditional Chinese Medicine philosophy, these practices help to promote the harmonious flow of vital energy (prana and qi) throughout the body, and help to regulate the functional activities of the body through regulated breathing, mindful concentration and movement. The integration of mind and breath helps to boost mindfulness, promote flexibility, and an increasing number of studies have also demonstrated the effectiveness of these practices on reducing levels of stress, anxiety, and depression.

- Individuals with limited mobility may find Qi Gong and Tai Chi to be a great alternative to Yoga, as the latter tends to require more strength, balance, and stretching.

Breathwork

- Breathing exercises are one of the quickest ways to activate the parasympathetic nervous system. As the only involuntary bodily mechanism governed by the autonomic nervous system that we also have conscious control over, breathing in a manner that simulates how we feel when we are at ease sends a signal to our brain to calm down and relax.

- Practising techniques such as diaphragmatic breathing and lengthening your exhales can help to induce feelings of relaxation. The 4-7-8 breath developed by renowned integrative doctor Dr. Andrew Weil is an effective technique. Begin by exhaling completely through your mouth, then inhale quietly through your nose for 4 seconds, hold the breath for a count of 7 seconds, then exhale completely through your mouth for 8 counts. Practice this exercise four times.

Massage

- When stressed, tension builds up causing mental anxiety and muscular tension. The manipulation of muscles during a massage encourages them to relax and stretch, which improves blood flow. Massages also cause the release of mood-boosting hormones such as endorphins, dopamine, and serotonin, which explains the sense of wellbeing we feel after receiving one.

- Additionally, massages promote lymphatic drainage and help to clear metabolic wastes more efficiently. When metabolic wastes build up, they result in muscular fatigue, weakness, swelling and pain. Flushing them out reduces physical stress, which in turn reduces mental stress.

Nutrition

- Avoid nervous system stimulants such as caffeine and sugar.

- Incorporate adaptogens into your diet. Adaptogens are powerful herbs which help us recover from mentally and physically from short and long term stresses. They have different benefits, and depending on the herb, can help to boost immunity, improve wellbeing, combat fatigue, reduce depression and anxiety, and enhance mental performance.

- Some examples of adaptogens include ashwagandha (reduces stress and anxiety), astragalus (reduces fatigue), reishi mushroom (reduces stress and anxiety, and has antioxidative effects), rhodiola (fights physical and mental fatigue), turmeric (fights depression and improves brain function), tulsi (reduces physical and mental stress, as well as depression), and liquorice root (reduces stress).

With the easing of lockdown restrictions globally, I hope this article has given you a better understanding of how our nervous system works, and has provided you with some inspiration of techniques and resources to bring you back into a state of health and wellbeing.

References

- Astragalus. 2016

- Bankenahally R & Krovvidi H. 2016. Autonomic nervous system: anatomy, physiology, and relevance in anaesthesia and critical care medicine. British Journal of Anaesthesia

- Berman, M. G., Jonides, J., & Kaplan, S. 2008. The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychological Science, 19(12), 1207-1212.

- Bowler, D. E., Buyung-Ali, L. M., Knight, T. M., & Pullin, A. S. 2010. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health.

- Cervinka, R., Röderer, K., & Hefler, E. 2012. Are nature lovers happy? On various indicators of well-being and connectedness with nature. Journal of Health Psychology.

- Coley, R., Kuo, F. E., & Sullivan, W. C. 1997. Where does community grow? The social context created by nature in urban public housing. Environment and Behavior.

- Fisher JP et al. 2009. Central Sympathetic Overactivity: Maladies and Mechanisms. Autonomic Neuroscience

- Gunnars K. 2017. 10 Proven Health Benefits of Turmeric and Curcumin.

- Harvard Health Publishing. 2020. Understanding the stress response.

- Hovhannisyan A, et al. (2015). Efficacy of adaptogenic supplements on adapting to stress: A randomized, controlled trail.

- Keller A et al. 2012. Does the perception that stress affects health matter? The association with health and mortality. Health Psychology.

- Korn L. 2017. The good mood kitchen: Simple recipes and nutrition tips for emotional balance. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company

- Meier M et al. 2020. Standardized massage interventions as protocols for the induction of psychophysiological relaxation in the laboratory: a block randomised, controlled trial. Scientific Reports.

- McCorry LK. 2007. Physiology of the Autonomic Nervous System. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education.

- Panossian A, et al. (2010). Effects of adaptogens on the central nervous system and the molecular mechanisms associated with their stress—protective activity.

- Panossian A. (2017). Understanding adaptogenic activity: Specificity of the pharmacological action of adaptogens and other phytochemicals.

- Rea P. 2014. Introduction to the Nervous System. Clinical Anatomy of the Cranial Nerves.

- Ressler KJ. 2010. Amygdala Activity, Fear, and Anxiety: Modulation by Stress. Biological Psychiatry Journal

- Sah P. 2017. Fear, anxiety, and the amygdala

- Umberson D & Montez JK. 2010.

- Wachtel-Galor S. (2011). Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects. 2nd edition.

- Wang CW et al. 2014. Managing stress and anxiety through qigong exercise in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement Altern Med

- Weinstein, N. (2009). Can nature make us more caring? Effects of immersion in nature on intrinsic aspirations and generosity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 1315.

- Wright A. Chapter 6: Limbic system: Amygdala. Neuroscience Online.